Francis Greenacre

Nicholas Jones: Paintings 1990-91

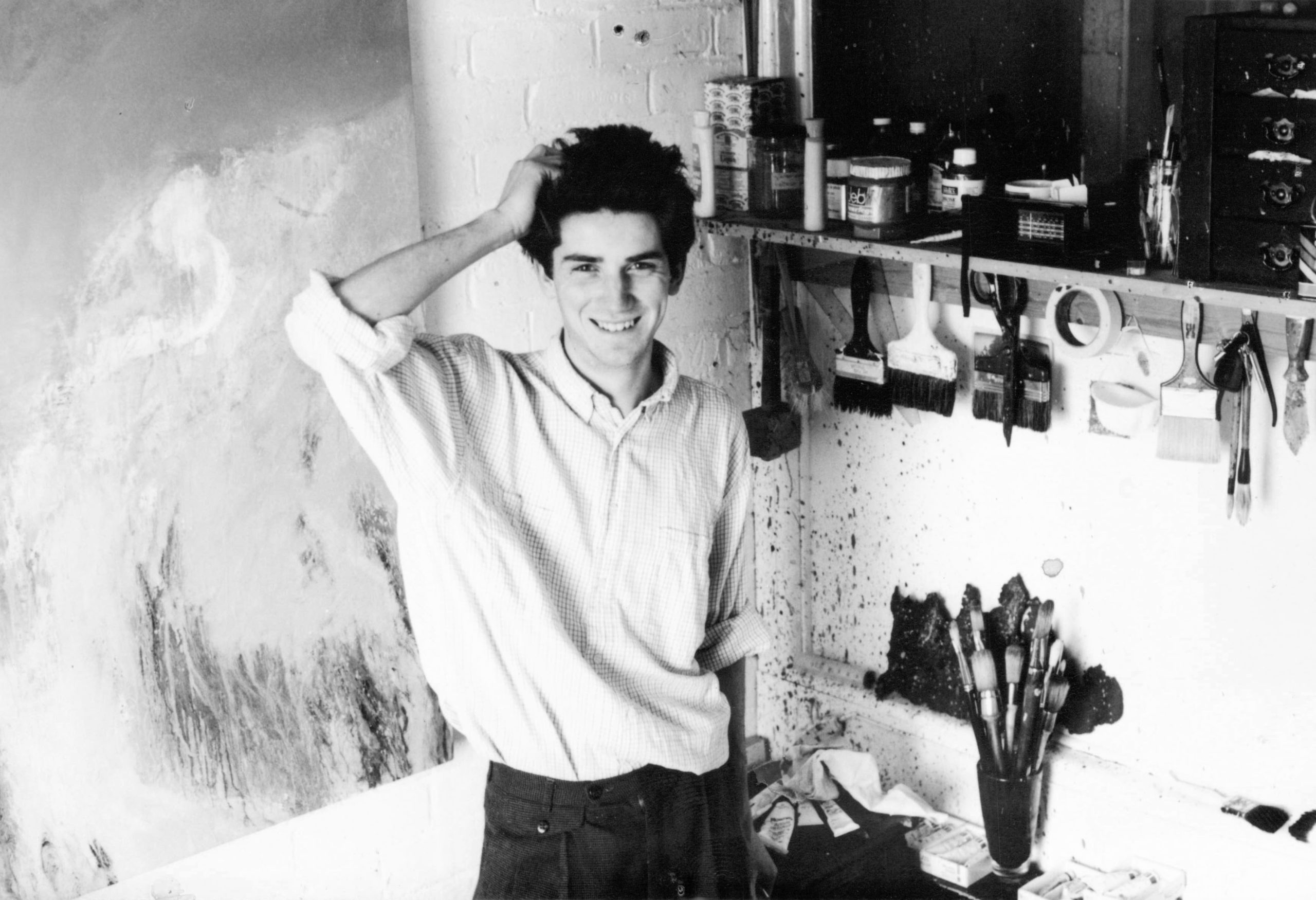

Nicholas Jones’ degree show paintings at Bristol Polytechnic in 1987 revealed a deep appreciation of Samuel Palmer and a concern for luminosity. That luminosity was obviously reflected in his interest in stained glass, and for two and a half years after college, Nick worked almost exclusively in that medium with considerable success. But in February 1990 he returned to painting, and this exhibition gives us a rare and fascinating opportunity to watch a painter, in the course of just twelve months, discovering his own artistic identity, working (and experimenting) with a sudden confidence, intensity and independence. He is still open to the influence of other artist’s work, as any good painter should be, but it is now only an occasional trigger, not a ponderous encumbrance.

Far more important is the inspiration of landscape itself, of his walks in the Pyrenees, in Mull and Skye and along Wainwright’s coast-to-coast path across the backbone of England. The paintings are sometimes recollections of these walks, but they are never records and they are far from the static images of an artist carefully selecting a specific view. They are a hill-walker’s paintings – the horizons are high, there is little sky. You look across or down, or are enclosed in a wood, and the landscape begins just beyond your feet. There is a sense of the shape and form of the landscape but also of passing through it.

As in ‘Precipice’ (Fig. 2) there are moments of breadth and grandeur, an almost visionary element, but there is also precise detail. The dramatic rock fissures in this work are paradoxically caused by rivulets of turpentine very delicately applied. There is evident delight in the way in which the turpentine is manipulated can lead to ambiguity, uncertainty as to whether the intention is abstract effect or actual illusion.

Like Alexander Cozens’ 18th-century blot drawings, Nicholas Jones often lets the form and detail of the landscape evolve from the painting process itself. He reminds us that the walker may be as aware of the random patterns and textures at his feet as of the broader effects of the landscape as a whole. In ‘Snow Scene’ (Fig. 3) the technique and calligraphic effect of the paint itself have a life almost independent of the image as a whole. Nick readily admits to an admiration for some of the abstract paintings by contemporary Japanese artists as well as for oriental calligraphy. At times he obtains paint effects in oil that are more familiar in watercolour. But the technique is still subservient to the coherent light effects throughout the panting – the memory of low misty clouds, moving against snow-clad hills, holding the light.

For an artist interested in light, who has also worked in stained glass, the woodland and plantation scenes may seem a natural progression. Light is almost as tangibly held within the branches (or the paint) as within coloured glass. In ‘Plantation’ (Fig. 4) the primary concern is the rich luminous rusty red. In ‘Firs’ (Fig. 5) it is the transparency of the light as well as the technique, the flicking on and scratching out of paint and the running down and rubbing out of turpentine that dominate.

In ‘Swollen River’ (Fig. 6) the artist seems to be putting back into his enjoyment of landscape itself, his admiration of British abstract expressionism, and in particular of the work of William Scott. The tense conjunction of the two rounded rectangles of the massive banks recalls some of Scott’s purely abstract work. For the first time the technique, the bravura brushwork and flicked paint, is directly concerned with the illusion of reality, the rushing tumbling waters and the spray.

It is as if knew well the work of Peter Lanyon (which he denies), the greatest painter of the Cornish Landscape, whose paintings also combined original and sensitive observation with a more vigorous abstraction and whose sweeping brush strokes echo the explosive meeting of land and sea. Lanyon taught at the art college at Bristol Polytechnic long before Nick was there. There is no specific connection between the two artists, but Nicholas Jones may yet join that select group of landscape painters who actually extend the boundaries of our appreciation of landscape itself.

Francis Greenacre

February 1991

Francis Greenacre is an art historian, fine art consultant, lecturer and author. He was formerly the curator of Fine Art at Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery.

This piece was written in 1991 as an introduction to an exhibition of my first paintings which was held in a 10,000 sq ft warehouse near Temple Meads railway station in Bristol.