Nick Jones

Reflections from Therapy

An exploration of the deeper currents shaping my journey as a painter

‘Art is a half-effaced recollection of a higher state from which we have fallen since the time of Eden.’ Hildegarde of Bingen

‘When the soul wishes to experience something she throws an image of the experience out before her and enters into her own image.’ Maester Eckhart

‘One does not discover new lands without consenting to lose sight of the shore for a very long time.’ André Gide

‘Painting is an attempt to come to terms with life’ wrote the 20C American artist George Tooker. Picasso once described it as being ‘just another way of keeping a diary’. For the last two years I have been working with a psychotherapist in an attempt to make sense of my life and put the pieces of the puzzle together. Reflecting on what is revealed or unveiled by the ‘diary’ of my paintings has been an important part of that process. As we have worked together exploring the life experiences and assumptions that have shaped my way of being in the world, I have noticed things beginning to shift and fall into place.

In his book ‘The Wild Places’ Robert MacFarlane mentions in passing how mapmakers in the 15th century developed the concept of the ‘isolarion’; ‘the type of map that describes specific areas in detail, but does not provide a clarifying overview of how these places are related to one another’ 1. I find that a helpful metaphor for the way we often experience our lives, and sense that through the therapeutic process the gaps in my map of self are beginning to be filled in. Understanding what my paintings reveal about the currents flowing below the level of my conscious awareness has been an important part of this ‘filling in’. In what follows I will attempt to explore and describe my evolving understanding of those deeper currents and the ways they have shaped my journey as a painter.

Earth and Fire

As I look back over that journey it seems to me that I haven’t really had much of a choice about what I have painted. The poet Theodore Roethke said ‘I learn by going where I have to go’, and that rather describes my experience, though I am now doing some of the learning retrospectively, and it has taken me many years to understand my own paintings.

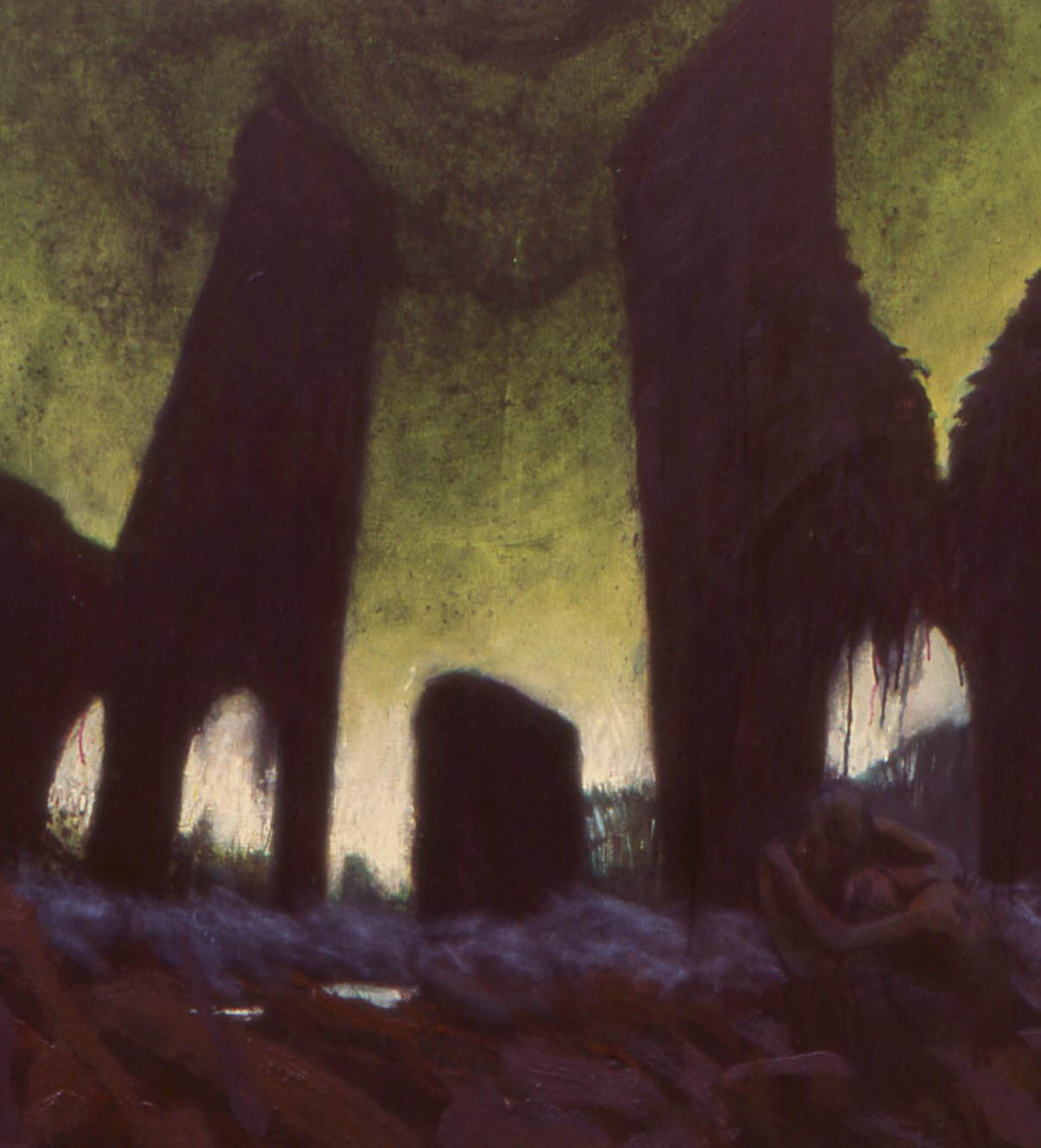

There was a period of about two and a half years immediately after leaving Art College where I had no clear sense of what I wanted to say, and so I hardly painted at all, working instead in the medium of stained glass. One of the few paintings from that period depicts the towering remains of a ruined building at twilight (Fig. 2). Clinging to each other in the dark foreground sit two naked figures. When I look at a reproduction of this painting after all these years, I feel surprisingly shaken and unnerved. It seems to be an expression of an inner desolation and aloneness that I now recognise to have run below the levels of my conscious awareness since childhood. That it should give itself form in that way I find remarkable. The mystical English painter Cecil Collins aptly observed that ‘it is not necessary to understand in order to create but it is necessary to create in order to understand’. 2

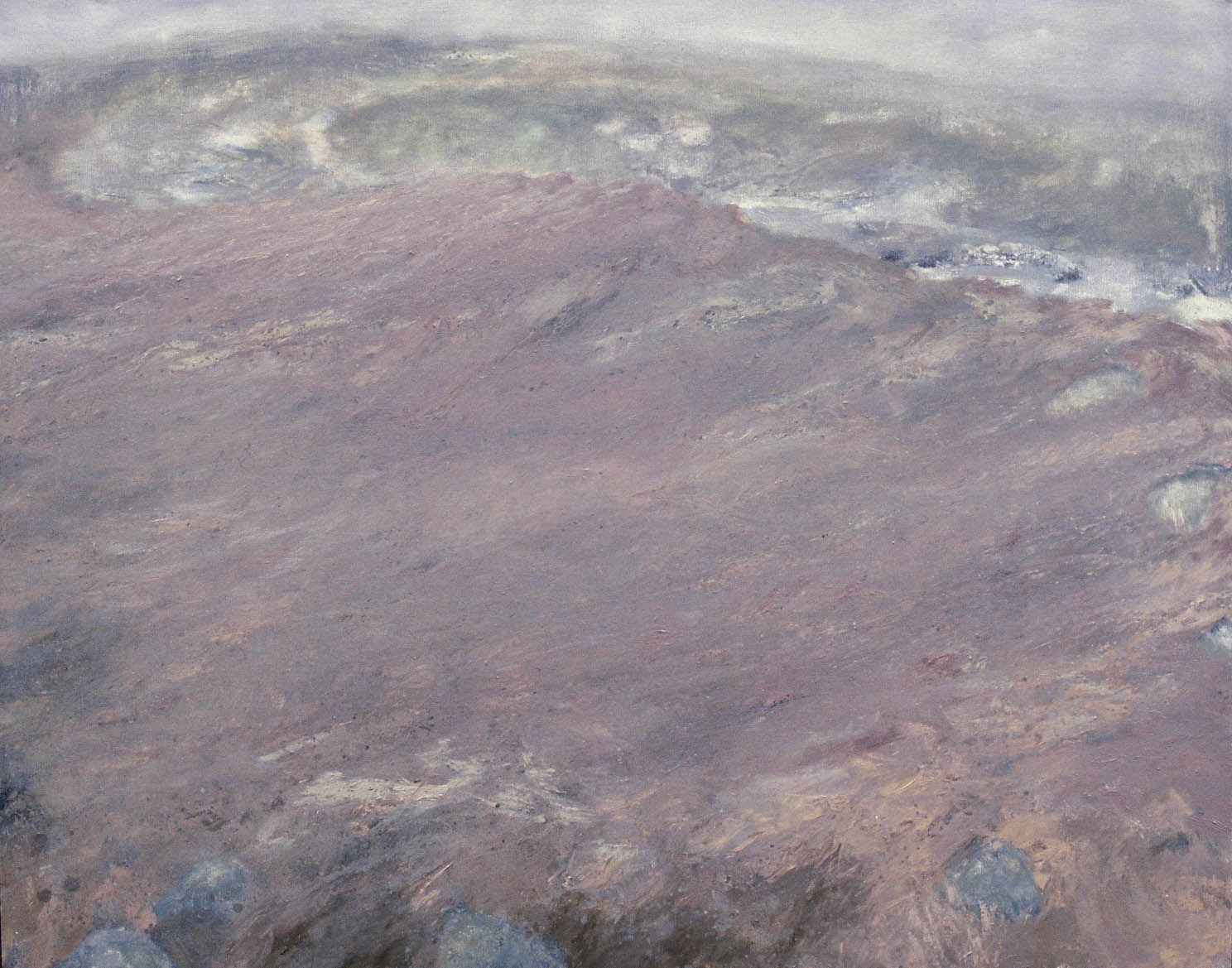

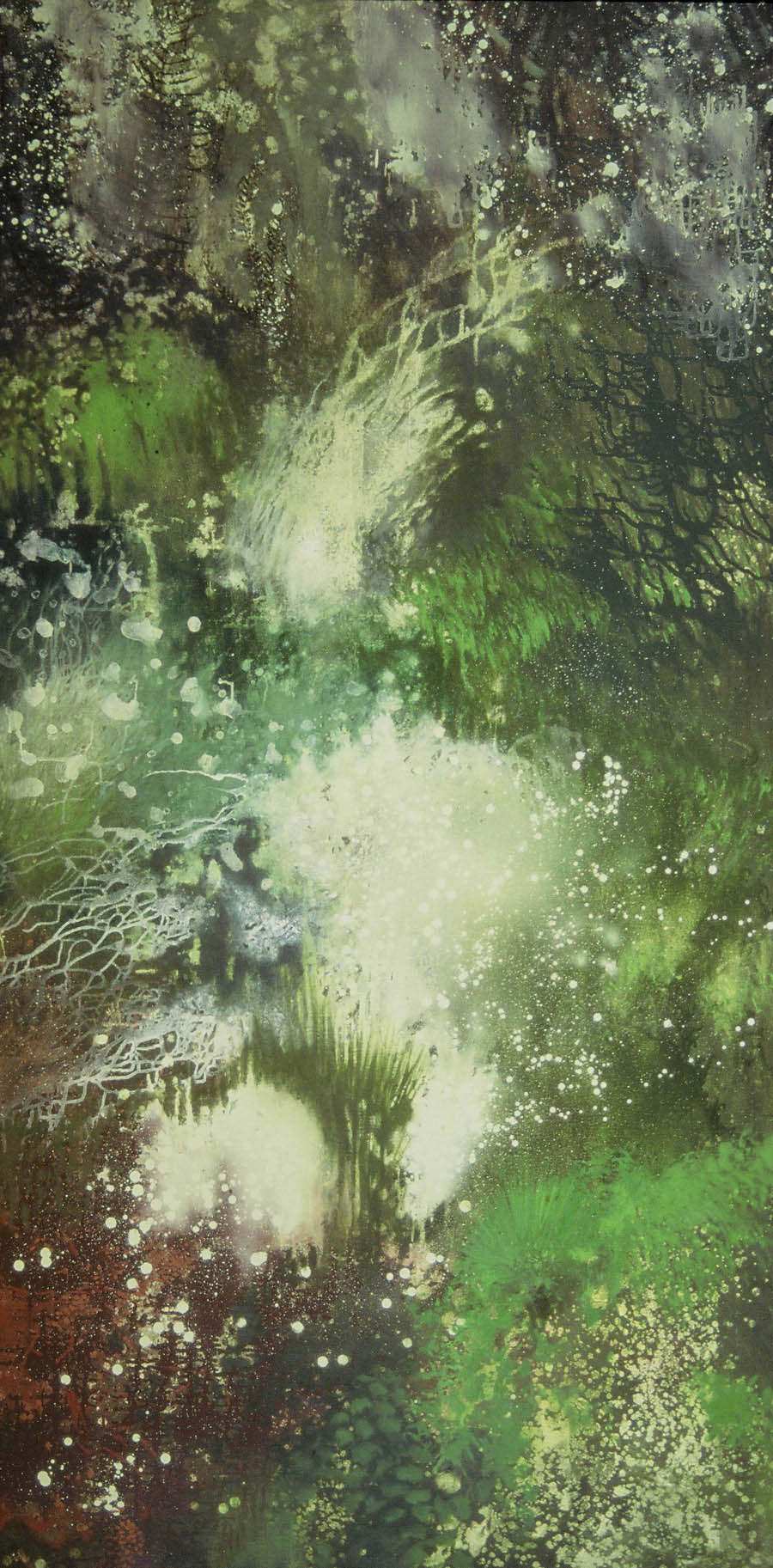

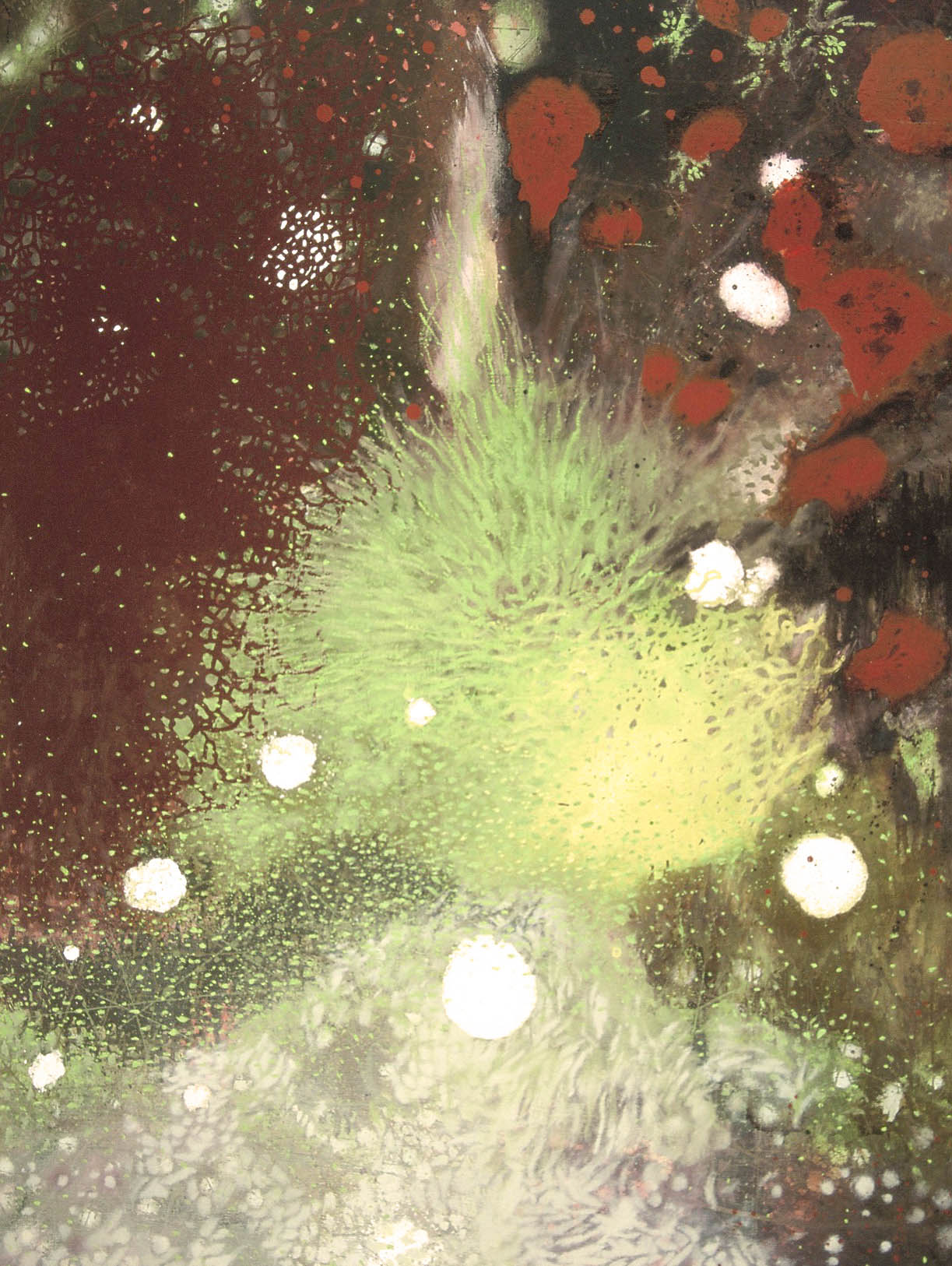

The drying up of stained-glass commissions at the end of 1989 coincided with, and perhaps helped prompt, a sudden urge to return to painting. Over the next twelve months there was an outpouring of bleak, wild, desolate landscapes, but this time with no evidence of human presence. I knew with certainty what I wanted to paint and was both surprised and delighted to find that I could do it. (Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5)

In the studio I felt a growing confidence, intensity, and independence. The studio environment and the painting process somehow enabled me to act and experiment with a boldness and energy that didn’t seem possible in the rest of my life. I allowed myself to make mistakes and learned that even when things don’t turn out as hoped, still nothing is wasted, rather new possibilities arise. It all felt deeply exciting and as if parts of me that had been unlived were coming into bloom.

Whenever my wife, Jane, had annual leave we used to go on long-distance walks in remote places: the Pyrenees, in Mull and Skye and along Wainwright’s coast-to-coast path, and the West Highland Way. These were my first real experiences of wild and sublime landscape and they impacted me profoundly. It all felt like a whole wonderful new world and the intensity of the feelings associated with those experiences is evident in the work.

The sense of new possibilities that I experienced both in the studio and in those early connections with wild landscape, were in stark contrast to my childhood and teenage years where so often I felt smothered, unseen, lost and inadequate. Life seemed to have a background colouring of heaviness and anxiety. My headmaster insightfully observed in my school report when I was aged ten that ‘the cares of the world seem to rest heavily on his shoulders – for no apparent reason.’ Here, instead I was experiencing the wild energy and grandeur of nature, and my own newfound capacity to channel my intense emotional response in the studio. To have those paintings admired at that early stage by such an esteemed figure in the London art world as Andras Kalman was an enormous encouragement and confirmation that I had begun to find my own identity as a painter.

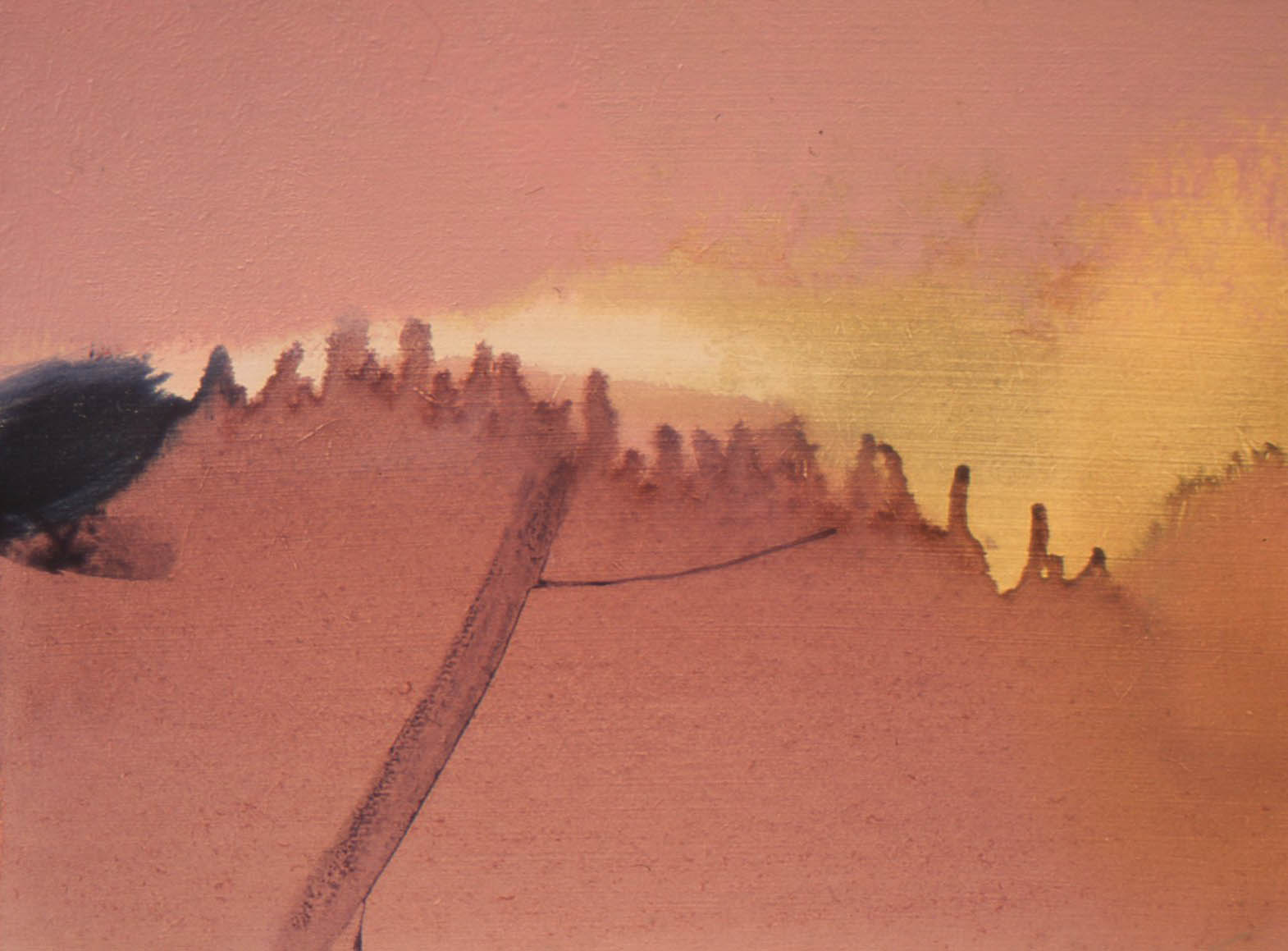

That intense first response to landscape then expressed itself in a series of paintings of fire (Fig. 6, Fig. 7). Up until now I have not known quite what to make of these paintings and so for many years wrote them out of my mental map of my journey as a painter; they just seemed too disturbing. But now, three decades on, they make more sense. They have something of an alchemical quality about them and form a natural bridge between those first landscapes and the powerfully energetic and gestural brush work of the paintings that followed. Given also that so much of my work has an elemental focus it was perhaps inevitable that I would at some point paint fire, alongside all the earth, water and air.

Abstract landscapes

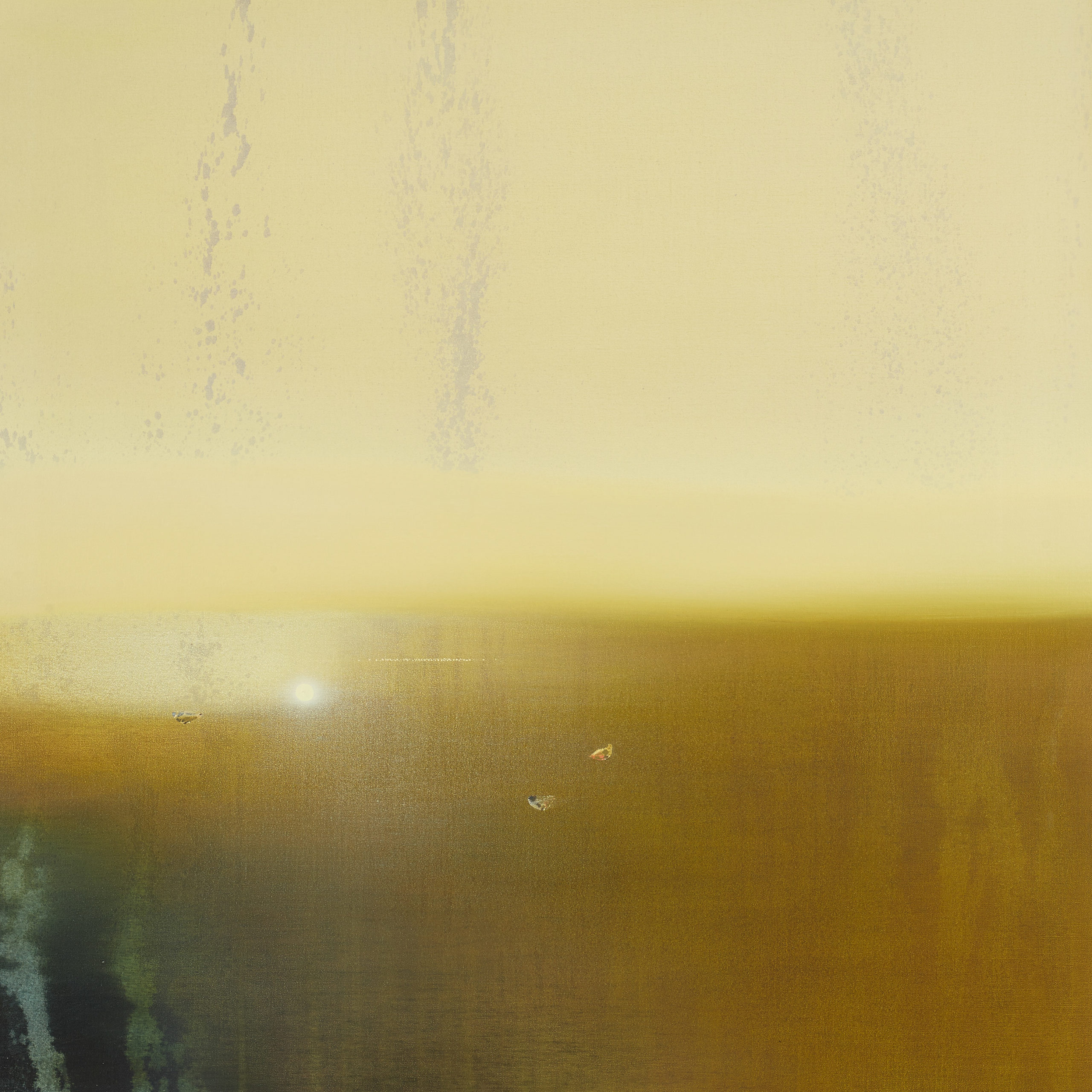

For the next two decades I continued to paint landscape exploring the terrain between abstraction and figuration. Generally, the direction of travel was from more gestural and energetic abstract works (Fig. 8) toward more spacious, luminous, ethereal, still and silent paintings. (Fig. 9, Fig. 10)

Once our children were born long-distance walks in remote places became a thing of the past. Instead I would take daily short walks down the lanes and through the fields and woods near our home and there were family holidays in beautiful parts of Devon and Wales. I felt a deep love for the natural world, and often experienced an ache of tenderness and wonder at the things I saw: reflections in the pond in the old orchard, the cycle of the seasons, the first star appearing over the hill and the ever- changing light. I was deeply touched by the sight of falling snow and frost on the grass, the return of the first swallows and the moon hanging in the twilit sky.

In a letter to his Polish translator Rilke wrote: ‘It is our task to imprint this temporary, perishable earth into ourselves so deeply, so painfully and passionately, that its essence can rise again “invisibly,” inside us. We are the bees of the invisible. We wildly collect the honey of the visible, to store it in the great golden hive of the invisible.’ Painting was for me a process of attempting to condense, distil out and evoke some of those intense experiences of beauty in the natural world, and imprint them deep within. I also hoped that those visible expressions might enable others to see with fresh eyes.

Over those two decades the painting process continued to feel very empowering and gave me a sense of self that was lacking in the rest of life. In the studio I could ‘be’ in ways that did not seem possible in other areas of my life. Looking back, I can now see that in those early gestural and vigorous abstract works I was connecting with, and learning to channel and express, a powerful inner energy in a safe environment. I could be spontaneous, direct, full of feeling, fearlessly experimental and free from the paralysing need to always be taking other people into consideration.

As my inner and outer life became more troubled and painful over time, so my paintings gradually became ever more serene and calm. I seemed to be searching for a quiet and spacious beauty and simplicity; a refuge of calm, silence and stillness (Fig. 11). As those qualities were largely missing from my external and inner life, the paintings became a kind of compensation or attempt at balancing things out. This is perhaps the process that Maester Eckhart was describing when he wrote ‘When the soul wishes to experience something she throws an image of the experience out before her and enters into her own image.’ Jung likewise believed that humans produce in art the images needed for their souls to transform. It is a principle that makes sense of much of my work and sheds light on many of the hidden currents that have shaped its direction.

Aurora

When I later travelled to Finnish Lapland in pursuit of the Aurora, I found the Arctic landscape staggeringly lovely. It was almost as if I had entered into the physical embodiment of that place of quiet, spacious beauty and simplicity that I longed for and was seeking to evoke on canvas. It felt so familiar; a world of water, trees and sky, silent and empty, bathed in the purest of lights. The stillness was so extraordinary. I can feel it even now.

At an intellectual level I used to explain my interest in the Aurora in formal terms. For an artist interested in abstraction, landscape, colour and light, I reasoned, the Northern Lights were a natural and wonderful subject matter. And indeed, in the Aurora, those four themes did come together in a sublimely beautiful way.

Inevitably there were also deeper currents drawing me in the Aurora’s direction. It was for me a time of increasing turmoil and difficulty and I longed for inner peace and harmony. Meister Eckhart wrote, ‘Truly, it is in the darkness that one finds the light, so when we are in sorrow, then this light is nearest to us.’ So perhaps the journey into the Arctic night was an enactment of an inner search to find light in the darkness. (Fig. 12, Fig. 13, Fig. 14)

Deeper still I was being pulled by a more paradoxical current. On the one hand there was an unconscious longing to be drawn out of myself into something bigger (as is commonly experienced by people witnessing the Aurora) 3 . On the other, I ached to access what Etty Hillisum describes as ‘the cosmic spaces locked away inside’ and ‘to delve down into the inner places where God keeps himself locked away’ 4. That seeming contradiction is perhaps not so contradictory after all, as Rilke experienced reality as being characterised by a vast, diaphanous fluidity between one’s inner most being and the unbound expanse of reality. 5

It is worth noting also that the Aurora paintings were by far the most figurative landscapes I had painted in twenty-five years. They were also the first in that time to have any indication of a human presence, even if that amounted to little more than a fire on a distant shore in only three of the works (Fig. 15). Up to that point it would have been inconceivable to me to contemplate including any sense of human presence and so the bonfires themselves came as something of a surprise to me. That said, it was insightfully pointed out to me recently that the small single spots of light or colour that frequently appeared as focal points in my paintings prior to the Aurora work could also be read as subtle indications of human presence. (Fig. 16)

This deep yearning for solitude is naturally part of the terrain for someone like me who is far down the introvert end of the spectrum. Though relationships with others are precious to me and I find them comforting and stimulating, extended periods of time spent in company can be very draining. Like all introverts I am most energised by time spent alone.

That however is not the full explanation of that longing for solitude. My rather underdeveloped sense-of-self and the porous boundaries that come with it are a more significantly complicating factor in my interactions with others. Over the years I have often been unclear about where I end and another begins. Depending on who the other is that can leave me feeling exposed and in danger of being swallowed up or losing myself. It is perhaps therefore not surprising that in my paintings I have been unconsciously creating spaces that are blissfully free of that risk. I took that approach to a whole new level in the Arctic paintings that followed those of the Aurora.

Arctic

The deep connection I felt with the landscapes of Northern Finland and the purity of its light stirred a desire in me to travel higher into the Arctic Circle and experience its vast emptiness and sublime grandeur.

In preparation for my 2018 Arctic Residency with the friends of the Scott Polar Research Institute, I spent 18 months working on series of paintings in which I explored this growing fascination with the Far North and tried to sift out what exactly the appeal was. The mesmerising qualities of Arctic light and the extraordinary ways it interacts with ice and snow became the primary focus. Many of the works focussed on the remarkable variety of optical phenomena that occur in arctic skies, and which evoke for me a sense of mystery and spiritual presence: solar and lunar rings, halos, and coronas, and the fog-bows, cloud-bows and rainbows that arc across Arctic skies. (Fig. 17)

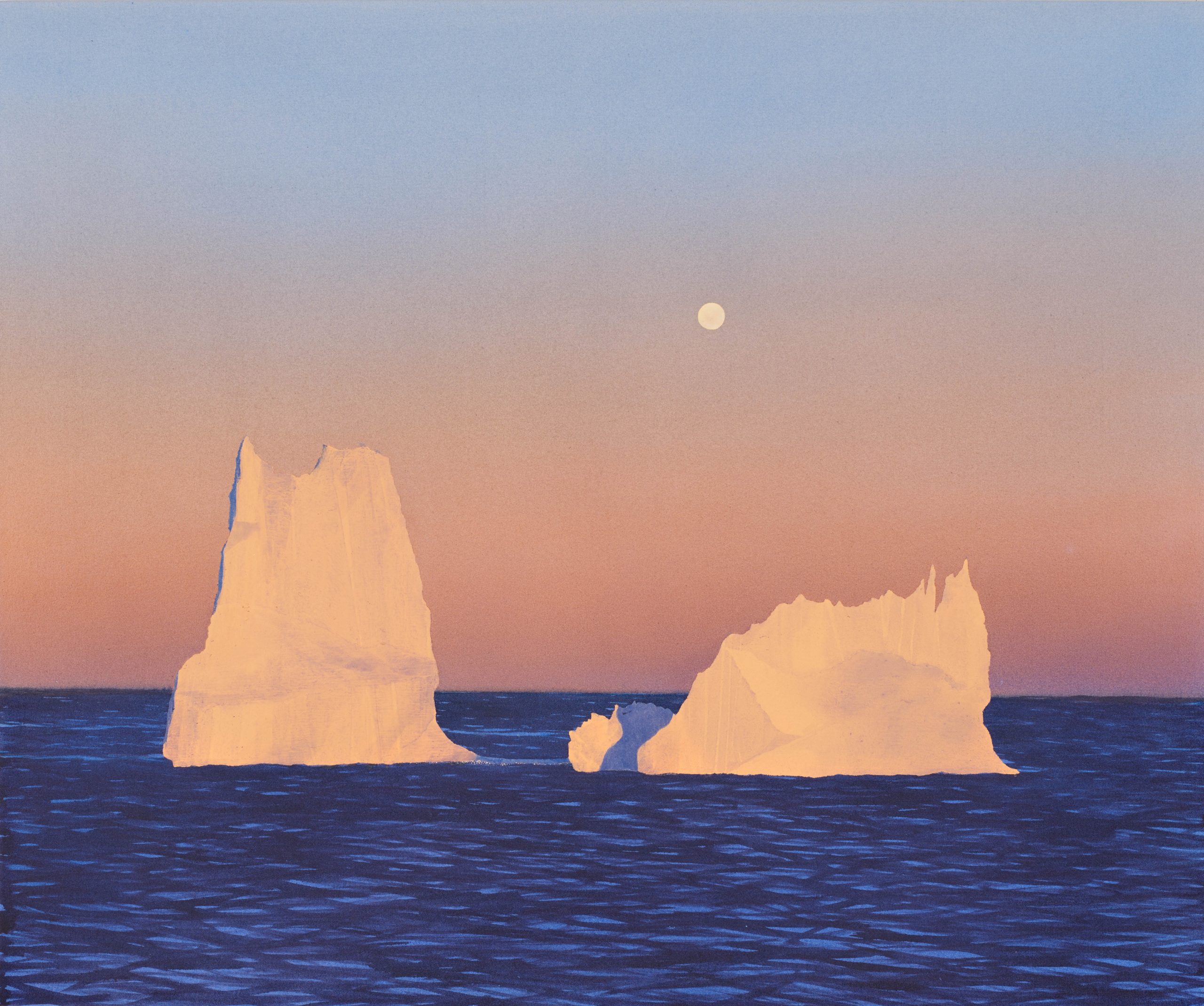

On an emotional and instinctive level, the fascination with Arctic landscape, was for me also an expression of a deep desire to escape from feeling smothered, limited and constrained and to break out into infinite space and light; to become free of that sense of oppression, and to be able to access an inner landscape of similarly spacious purity and grandeur. (Fig. 18, Fig.19, Fig. 20)

The two weeks I spent in Greenland and Baffin Island exceeded all my hopes and expectations. I found it exhilarating to be immersed in an environment made up of the simplest ingredients: ice, water, rock and light. Freed from the many distractions of normal life I felt an unusual clarity of mind and an increasing connection to the rhythms and wonder of the natural world. Not surprisingly the large body of work that flowed from it has a particular intensity.

The fascination with the icy world of the Arctic can be explained at many different levels. Perhaps the most obviously Jungian is to see it as a reflection of a desire to connect with the parts of myself that had become frozen through the inevitable woundings of childhood. I am increasingly coming to see the truth in this and recognise how I adopted ‘freezing’ as a defence mechanism to ensure my survival. Strangely, and rather wonderfully, something shifted and softened in me whilst I was actually in the Arctic. When I met my therapist for the first time after my return, at the end of the session she looked at me with a kind of surprised wonder and exclaimed, ‘You had to go to the Arctic to thaw out!’

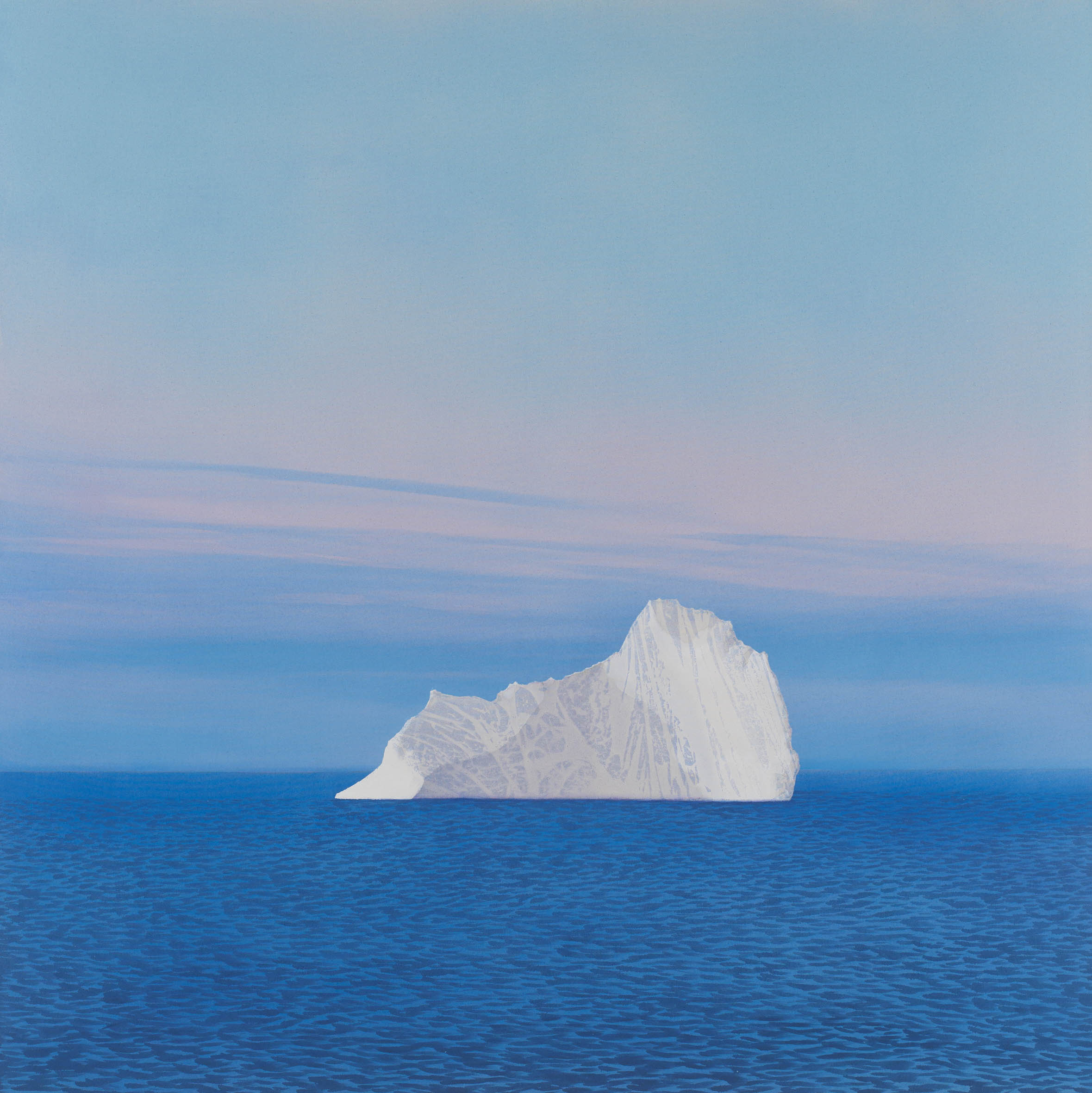

At a symbolic level I find icebergs to be beautiful images of trust, surrender and letting go, all qualities that I aspire to. Once an iceberg has calved from the glacier or ice shelf from which it was formed, it trusts itself to the elements; the wind, waves and ocean currents. It may for a while be grounded in water too shallow to support its immensity, but in time it will be carried out to sea on the ocean currents allowing itself to be shaped and sculpted by the flow of time, tide, wind and weather.

I find icebergs extraordinarily beautiful and moving to look at. They seem so composed and contained, utterly at ease and wonderfully responsive to the changing light and colour of the sea. Frederick Edwin Church, the great Luminist painter, considered icebergs to be the very embodiment of light in nature. 6 (Fig. 21, Fig. 22)

Over time an iceberg gradually thaws, breaks up and releases the sediment that it has been carrying and so enriches the ocean bed. Though the form of an iceberg is continually being altered by the elements, the berg quite naturally maintains its balance, sometimes rotating dramatically in the water to reveal parts of itself that had long been submerged, and thus regains its equipoise. Ultimately, however, it surrenders itself into something bigger – the greater flow and oneness from which it came.

It has taken some time for the symbolic significance that I attach to the Arctic and to icebergs in particular, to come into focus. I now sense that an inner work of expanding, thawing and letting go has been quietly going on in the background as I worked on my Arctic paintings.

Mark Making

In plotting the twists and turns of my journey as a painter alongside my own life story, there is another interesting parallel to which it is worth drawing attention. It relates to the gradual elimination of gestural or expressive brush work in the paintings over time.

Initially there was a powerful surge of energy as I began to find my voice as a painter, beginning with the wild landscapes of 1990 and the ‘Fire’ paintings of 1991. That wildfire energy morphed into the expressionistic brush work of 1992-94 (Fig. 23) and then settled into the calmer and more carefully considered calligraphic mark-making in the second half of the 1990’s (Fig. 24). From 2000 brush work and mark making began to disappear from the work and by 2010 it had all but vanished. (Fig. 25)

To some degree I was aware that this was happening, and in my catalogue introduction to the ‘Light’ exhibition at Crane Kalman in 2014 I stated that I was deliberately trying to ‘leave little evidence of brush-work or my own hand’. On reflection, I now sense two currents underlying this development in the work. Firstly, I increasingly wanted the works to evoke an atmosphere of inner silence and stillness; to be objects for contemplation, with their own intangible music, fragrance and sense of spirituality. I reasoned that I did not want to come between the viewer and the painting, and so attempted to step out the way by erasing obvious signs of my involvement in making the work.

There is, however, also an intriguing parallel with what was taking place in my life outside the studio, which may have more unconsciously influenced this elimination of mark making. As life became more and more difficult for me from 2000 onwards, it seems that I may have adopted my childhood defence mechanism of trying to ensure my survival by wiping myself out of the picture. Having little sense of self or confidence in my agency, it felt safest to become invisible, which is, in a way, what I was seeking to do in the paintings also.

After the inner thawing that took place during my Arctic journey, a very natural and seemingly effortless calligraphic mark-making began to appear in the handling of water in my Arctic paintings (Fig. 26). This was also shortly after I began working with my therapist. I find this to be an encouraging sign and it will be intriguing to see how this return of more expressive mark-making in the painting evolves in tandem with the therapeutic journey.

Loss and Seeing

As I have surveyed my output from the last three decades, I have been struck by how virtually every work I have produced is an evocation of a seemingly pure and pristine landscape, undefiled by human activity or destruction. Below the surface of the work I sense an ache of longing for something that has been ‘lost’ or ‘lost sight of’. Hildegarde of Bingen observed in the 12th century that ‘Art is a half-effaced recollection of a higher state from which we have fallen since the time of Eden.’ When I came across those words recently, they seemed to shed a new and unexpected light on a certain intangible quality to my paintings.

Associated with that ache of loss I also sense a longing to be able to see the things that have been ‘lost sight of’. I clearly remember a walk I took thirty years ago on the Clifton Downs in Bristol. It was a beautiful spring day and I was looking down into the spectacular Avon Gorge spanned by the Clifton Suspension Bridge. As I surveyed all that wonder I distinctly remember feeling that somehow, I just couldn’t see it; that I was missing something; that I wasn’t present at all. It was an experience that was repeated often and is perhaps akin to that described by Wordsworth in his lines:

But for those obstinate questionings

Of sense and outward things,

Fallings from us, vanishings;

Blank misgivings of a Creature

Moving about in worlds not recognised. 7

Antoine de Saint-Exupery, in his novella ‘The Little Prince’, writes that ‘It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.’ I suspect that for me the creative process has been a working out of a longing to be more present and connected to the unseen, and the manifestations of the Divine Presence in the world around. By working instinctively, guided by ‘the eye of the heart’, it was my hope that I might be able to evoke or unveil aspects of the spiritual nature of reality that we so often miss in our perennial busyness. This longing to recover a more direct perception, to be able to see with the wonder of a child, as if for the very first time, was something that I was conscious of as an Art Student and wrote about in my degree thesis. Though in some ways I lost sight of it for many years, I sense that it has been at work below the level of my conscious awareness shaping my journey as a painter ever since.

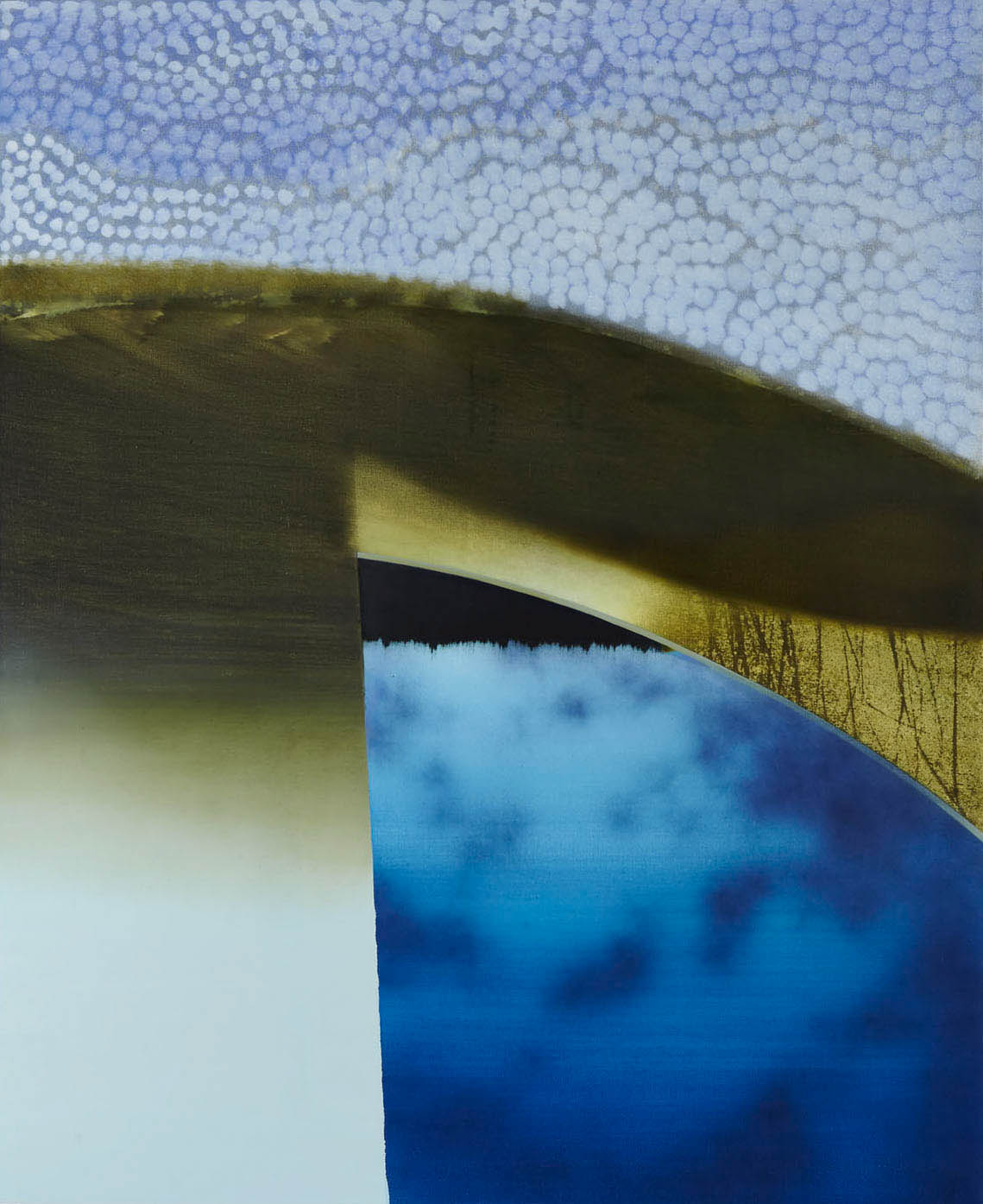

Beginning in around 2005 I began to introduce into my paintings some hard edges: sweeping curves and interlocking shapes, in which different worlds, elements of landscape, or states of being were held together in one image (Fig. 27). I enjoyed playing with the crisp, bold abstract shapes and the pattern and texture, however these paintings puzzled me, and I felt a little uncomfortable about the severity of the edges. But now, given how that underlying desire to see beyond the surface has come into focus, they feel like a kind of peeling back of the layers of reality; the crossing of a threshold into territories of otherness, and an attempt to hold those contradictions together in oneness.

My use of hard edges seems to convey something of the nature of hard, or even jarring, boundaries between different ‘worlds’, or states of consciousness. In a correspondence with a friend about these ‘hard edge’ paintings she made the following comments about ‘The Mingled Chorus’ (Fig. 28), a painting from 2006 that she lived with for many years:

‘The part above the ‘hard edge’ straight line had much of the quality of your later ‘Light’ paintings, and always spoke to me of spiritual light. The part below the hard edge, on the other hand, where the black resided, always spoke to me of the darknesses and sense of chaos which characterise the troubled (and sometimes hellish) elements in human experience. The painting somehow conveyed to me a clear and unambiguous certainty that the Light always wins – that it is the Light which actually always has the power, despite human experience seeming sometimes to be in chaos or darkness.’ 8

She also wondered if my use of hard edges may be related to my experiences of struggling with issues relating to the boundaries of my identity and others, and the way that personality boundaries can be associated with clashes, but are also essential to survival as an individual. Where I managed to hold these contradictions together in oneness in a painting, it gives a glimpse of how sometimes ‘jarring bits of chaotic experience can suddenly resolve into one harmonious whole, accompanied by a sense of joyous oneness and peace’. (Fig. 29)

Longing

As I have sought to map out this unfolding journey, the deep ache for silent spaciousness, inner unity, a firm foundation, and a gentle but irrepressible aliveness, has come more clearly into focus as a powerful tidal flow shaping the development of my work over the years.

David Whyte describes longing as “divine discontent; the unendurable present, finding a physical doorway to awe and discovery that frightens and emboldens, humiliates and beckons, makes us into pilgrim souls and sets us on a road that starts in the centre of the body and then leads out, like an uncaring invitation, like a comet’s tail, felt like both an unrelenting ache and a tidal pull at one and the same time…” 9

As this longing was giving form to itself in the paintings, it was also curiously being brought to the surface in a parallel way through a friend who seemed to embody those very qualities for which I so unconsciously ached. For much of the last thirty years, I simply have not known what to do with the feelings of emptiness and longing stirred up by her presence in my life, nor what they might mean. It was indeed a confusing, humiliating and unwanted experience, but also one that seemed stubbornly significant and hard to avoid. With the help of my therapist, I have begun to understand something of what was happening, and how, by simply being herself this good friend was awakening me to large parts of myself that were missing or asleep, and calling them out of me. It was, my therapist explained, what Jung would call a classic ‘Anima projection’ 10. I find it remarkable how closely the qualities that she seemed so luminously to embody paralleled those that I unconsciously recognised to be lacking in myself, and for which my paintings became a compensation.

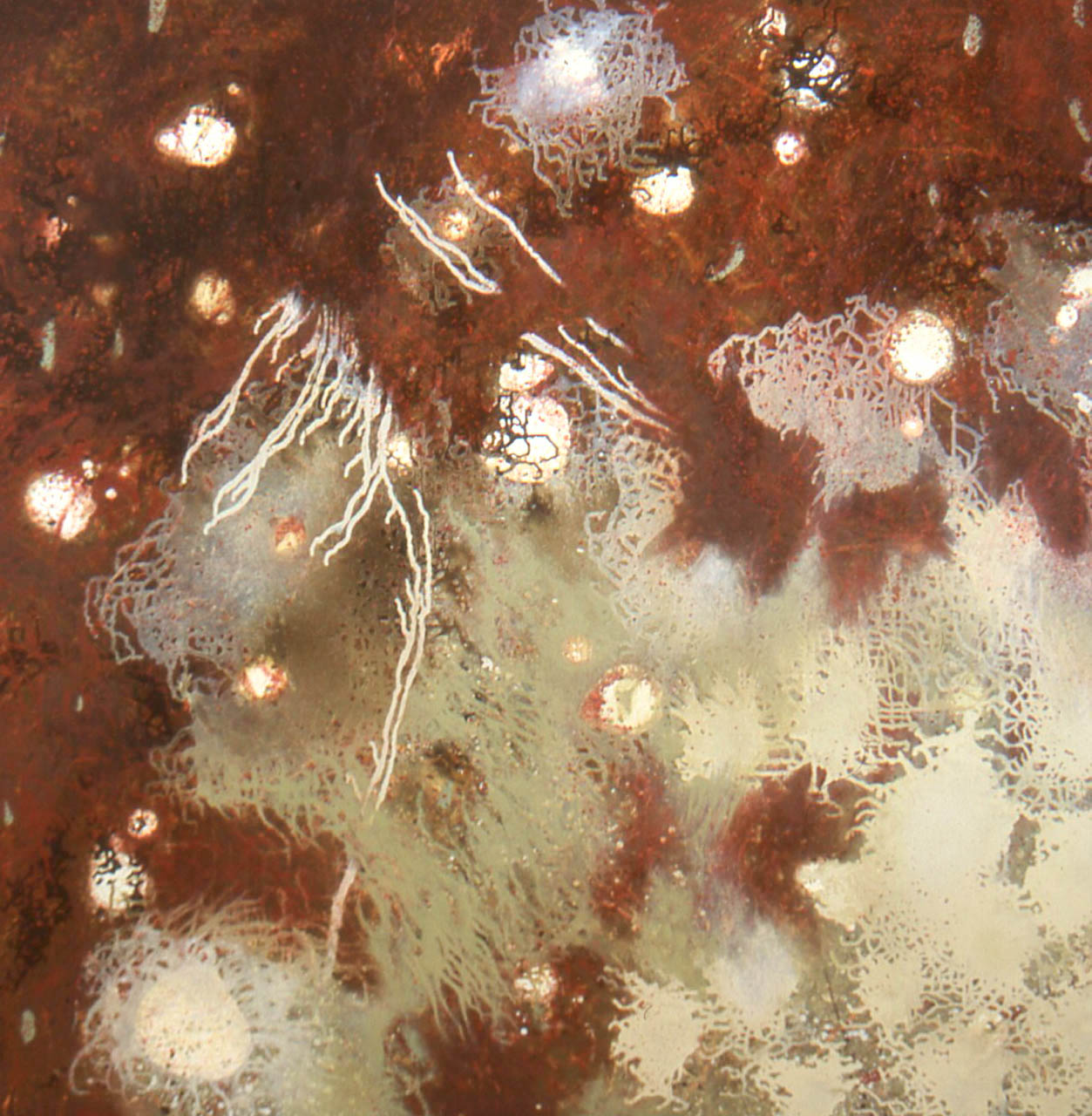

In 1992, shortly after our paths first crossed, I produced a series of paintings depicting luscious undergrowth, mossy cascades and fertile watery worlds (Fig. 30). At the time I was unsure where those paintings were coming from, but one of them (Fig. 31) was a conscious attempt to channel or perhaps release the powerful feelings that had been stirred up in me. Once it was completed, I began to feel uncomfortable about having so consciously tried to express those confusing feelings in paint, irrationally fearing that they may amount to a kind of marital infidelity, and so I destroyed it. It has taken many years to understand that painting, but as I look at a reproduction of it now, I sense it to be an invitation to cross a threshold into otherness; into the mysterious depths of an inner world that was then foreign to me, and from which I was excluded. It evokes for me both a warm and intimate web of feminine fecundity, softly holding luminous treasures, and a sense of cosmic vastness. 11

Nearly three decades on, I sense that enough inner thawing has now taken place to enable me to begin embracing and integrating at least some of the dormant feminine parts of myself which she has been embodying and calling out of me all this time. As I have done so I have noticed the ache of inner emptiness gradually begin to dissipate and, in its place, a sense of intimacy, fullness and warmth slowly taking shape. It feels as if the inner emptiness is slowly but wonderfully beginning to change into an inner spaciousness, and those qualities that she so luminously seemed to embody, I am now beginning to find within myself.

Reconnecting with that painting in this way, I can now see how the other works from that period were also being shaped by this unconscious longing to find my own aliveness and sense of inner spaciousness and abundance. (Fig. 32)

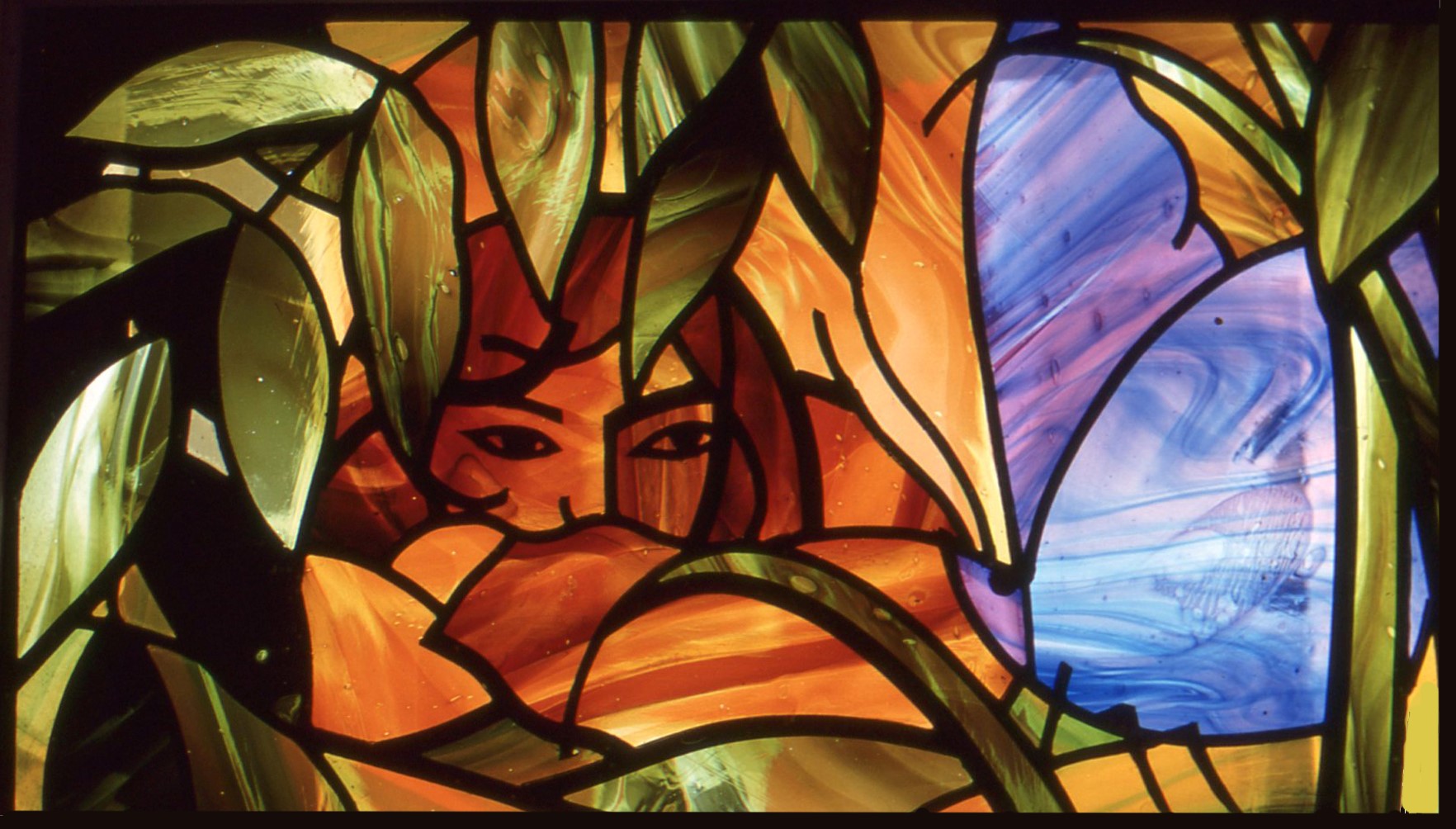

Art College and Stained Glass

The only work I have not yet referred to is that done at Art College and in the two and a half years immediately following. During my Foundation Year at Art College, I made two important discoveries. Firstly colour, and secondly landscape. Up to that point I had been extremely tentative about using colour. This reticence was perhaps not surprising given that I have long been dogged by a sense of invisibility and nothingness. Making bold, confident statements did not come easily.

I distinctly remember a conversation with the painting tutor, Neil Murison, about a table top still life I was working on, in which he helped me to see the vast difference between the rich colouring of the objects before me and the chalky tints I had used in my painting. That new seeing triggered an explosion of colour in my work (Fig. 33, Fig. 34). This was coupled with a loosening of both brush work and general approach as I enthusiastically experimented with painting landscape en plein air during field trips in deepest Somerset and Cornwall.

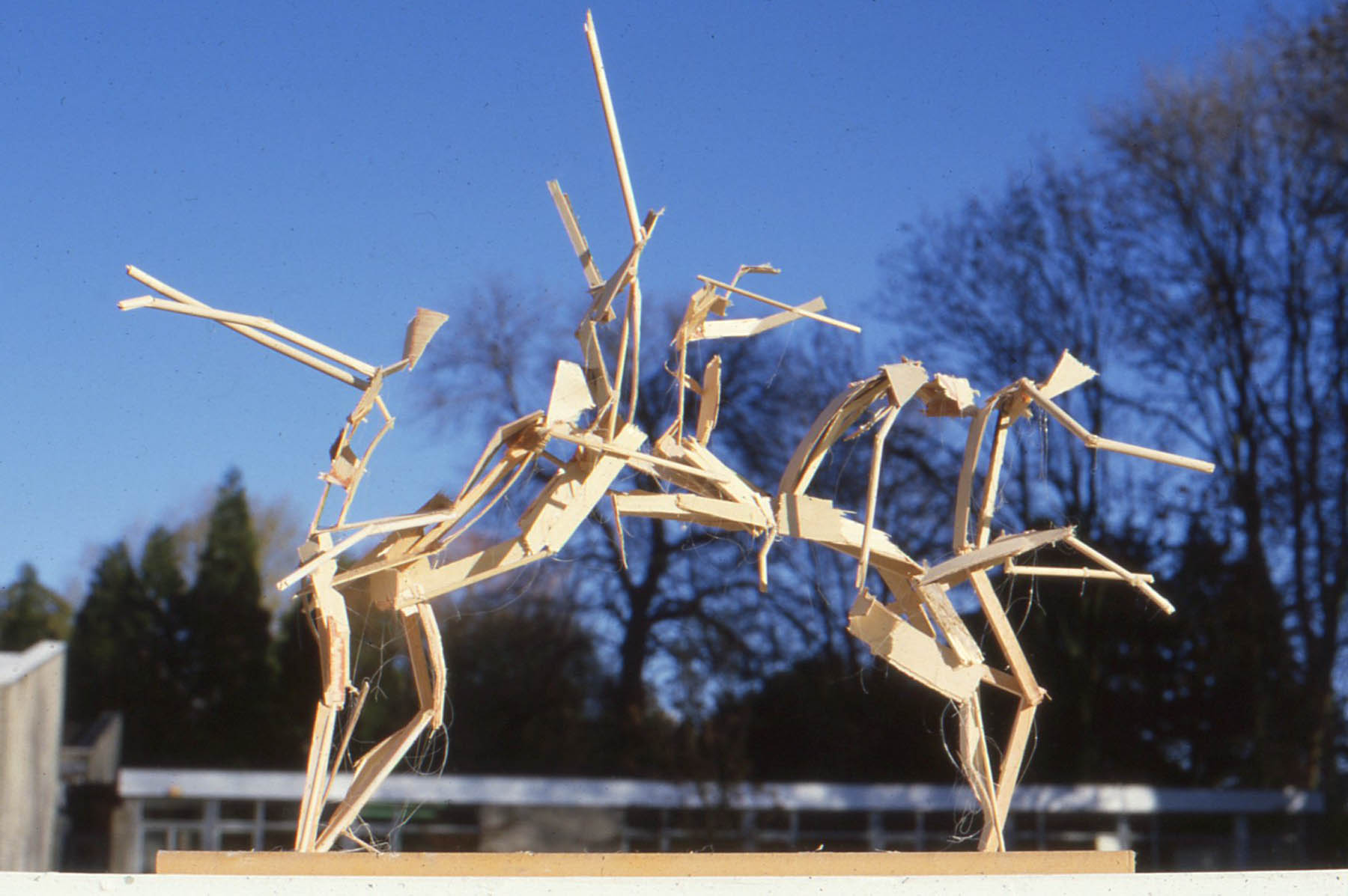

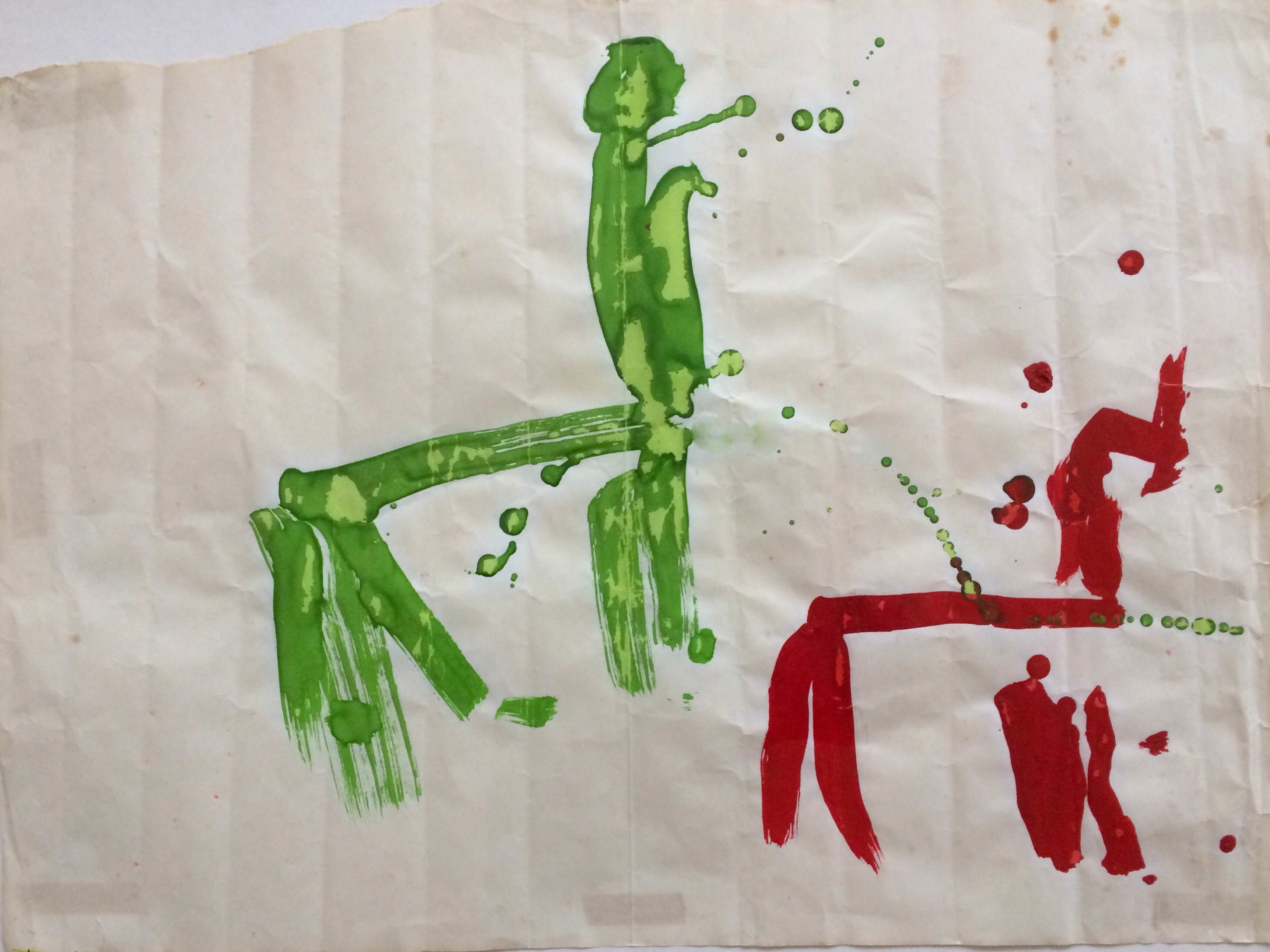

One’s twenties are a confusing time – full of potential, experimentation and discovery, and yet oscillating between self-belief and uncertainty. These conflicting currents were reflected in the work that I produced during my Fine Art Degree at Bristol. The impressionistic and lively landscape painting continued, but I also enjoyed working in three dimensions producing playful sculptures about movement and flow (Fig. 35) depicting dancers, gymnasts, animals and exhilarated figures seemingly breaking free from their bonds. Later there was a darker and more melancholic seam of paintings: self-portraits walking alone in the night prefiguring the ruin painting referred to earlier.

The prospect of the looming Degree Show focused my mind on producing a more coherent body of work. What took shape was a series of luminous paintings of moonlit gardens or fields often with a solitary and sometimes sleeping female presence. Influenced by the work of Samuel Palmer and the mystical English painter Cecil Collins I sought to evoke an atmosphere of stillness, intimacy and magic. As well as the female presence the paintings sometimes depicted other archetypal imagery: fountains, archways, birds, but most often the moon. In the final show there were also some pieces of stained glass and a painted window (Fig. 36) exploring similar themes, along with a series of monotype drawings of mostly female figures, which I consider to be the strongest work. (Fig. 37)

Having grown up in the very masculine world of the boy’s boarding school where my father taught and where my two brothers and I were educated, there was not much feminine softness or attunement around. As a sensitive and thoughtful child this was not an easy environment for me, or one that nurtured my more unconscious feminine qualities. I now recognise these paintings as being the first stirrings of a deep subconscious desire to be more connected to that lost and more feminine side of myself; my Anima, to use Jung’s name for the unconscious feminine side of a man.

For two and a half years after leaving Art College, though I wanted to be a painter, I did very little painting because I simply did not know what I wanted to say. Instead I worked in stained glass and continued to explore the themes of my college work. It was a joy to work with pure colour and light and to draw with the crisp clean lines of the leadwork. Then in 1990, as described earlier, I abruptly stopped the stained glass and took up my brushes and found a voice.

As I discussed with my therapist the meaning of that two-and-a-half-year pause, she speculated that perhaps it was a protected stage of development; I withdrew for a while, and then suddenly, as with a butterfly, something completely new and different emerged from the cocoon.

It was a suggestion that resonated with me, and as I reflected on it later, I recalled that one of the windows I had made at that time actually depicted a woman (with a distinct resemblance to Jane) gazing intently at an oversized butterfly. (Fig. 38)

One of the last windows I made was an image of Pegasus, the fabled winged horse of Greek mythology who was capable of creating streams of water wherever he struck his hoof (Fig. 39). ‘At least two famous springs in Greece, both named Hippocrene (“Horse Spring”), were widely believed to have been issued forth by Pegasus’ hoof. The more famous one of the two was located on Mount Helicon, the sacred abode of the Muses; its waters, when drunk, enthused poets with inspiration and creativeness.’ 12 In the light of my therapist’s suggestion those two windows seem to be an intriguing piece of synchronicity.

Animal Being

As a child and teenager animals held an important place in my life. A painting from when I was two years old depicts with calligraphic simplicity a couple of horse-like creatures in red and green (Fig. 40). We lived a stone’s throw from Bristol Zoo and from my bedroom I could hear lions roaring and the eerie whooping call of the gibbons. I avidly collected weekly ‘World of Wildlife’ magazines, and as a teenager I would visit the zoo most days and drink in the wonder of all those extraordinary creatures, which I would often draw. In my final years at school I made a series of ceramic animals: giraffes, birds, a slippery looking frog on a stone, and a large bear whose ears had to be filed down slightly in order to fit her into the kiln (Fig. 41). Animals also featured often in my stained-glass work.

As part of my Biology A-level studies I did a study of the Crab Eating Macaques in the monkey temple at the Zoo. Guided by a university student I learned to recognise each member of the group and spent hours recording, at 15-minute intervals, who was grooming whom. Monkeys spend many hours a day lovingly and carefully grooming each other, thus building social bonds through the power of touch. The patterns of grooming reveal the detailed hierarchy of the social structure of the group. I took solace from their company and suspect that there was something about the intangible sadness that can be seen in the eyes of animals (and the captive state of these particular ones) that echoed somehow.

Part of the draw that animals had for me was to do with the way that animals seem ‘know this world in a way we never will’, as John O’Donohue beautifully puts it. They live entirely in the present moment always ‘looking out from the here and now’ and ‘walk upon the earth with a confidence and clear-eyed stillness’ 13 that I still find deeply attractive. I loved the verse from the book of Job that says, ‘But ask the animals and they will teach you’. 14 The ceramic frog that I made when I was sixteen has special significance for me now given that, like a good meditator, it remains for hours in a motionless position without ever loosing awareness of life around it. (Fig. 42)

A while back my therapist intuitively suggested that I might try booking a massage. It took me a while to relax into receiving that special kind of touch, but I now so appreciate the way it helps me to be a little more ‘in the present moment’ and ‘in the body’ in the way that animals so effortlessly are.

Looking Forward

My therapeutic journey to date has been a process of increasingly recognising the connections and putting the pieces of the puzzle together. Though life is inevitably full of mystery I am coming to see and trust that there is a deeper coherence underlying it all. There is always a good reason why we do the things we do, even if they are destructive or self-defeating. As I have begun to fill in the gaps in the map and to hold the whole, whilst being ‘held’ by the therapeutic relationship, a measure of healing and integration have started to come.

Painting has been an enormously important part of my life, and I am very grateful to have been able to pursue this path. It has, I feel, literally held me together. Not only has the studio been a sanctuary and refuge, but also a nursery, in which I have sought to explore and grow. It has enabled me, as Meister Eckhart said, to give form to the images that my soul sought to enter into.

In this light I now recognise that the unifying current unconsciously driving my painting through all its different phases over the past three and a half decades has been a powerful sense of longing to find and come home to myself. In his Consolations essay on ‘Longing’ David Whyte describes that journey thus, ‘In longing we move, and are moving, from a known but abstracted elsewhere to a beautiful, about-to-be-reached someone, something, or somewhere we want to call our own.’ 15 The therapeutic journey has brought that into focus and led me closer to the shore of that new land. I recognise that there are many things that I do not yet know about myself and that there are deeper layers and slower rhythms of awareness yet to be discovered. Naturally this new seeing brings with it a sense of grief for what has been unlived or lost but that is all a necessary part of the process. As Andre Gide wrote, ‘One does not discover new lands without consenting to lose sight of the shore for a very long time.’

I feel a sense of quiet excitement and anticipation as I stand on the threshold of that deeper inner life, and am beginning to sense how that ‘going inward’ may play out in my future work. Ralph Waldo Emerson observed that ‘What lies behind us and what lies before us are tiny matters, compared to what lies within us.’ As I more consciously seek to explore the wide and open landscape within and find a solid resting point there, I suspect that my paintings might from now on become more conscious and lyrical explorations of that inner landscape.

For over two decades my approach to painting was largely instinctive and spontaneous; the paintings unfolded gradually or suddenly from the unknown in a kind of improvised dance. With the Aurora paintings and the Arctic work that followed, I adopted a much more structured and planned way of working. I suspect that this was something of a surprise to many people, as it was to me also. That change in approach, however, occurred shortly after the ground seemed to really fall away from beneath my feet in my personal life. I suspect that I instinctively adopted a more structured way of working to hold me through a time of enormous uncertainty and confusion. The resulting works were a very real anchor in that time of transition. Now that I have completed the Arctic works and, thanks to the therapeutic process, am finding the ground more solid beneath my feet, I sense that I am ready to plunge into the unknown again and be taken wherever it wants me to go.

Postscript

This journey of awakening to the unconscious currents that have shaped my painting and to begin weaving them into a whole has been full of unexpected insights and ‘ah-ha’ moments. It is all far more connected than I ever thought it could be. Lately, there has been one more discovery that feels particularly significant. It concerns the way in which I relate to my completed work, both as a whole and individually.

Over the years I have tended to avoid looking too closely or long at my completed paintings, and I generally feel quite disconnected and remote from them. I often find myself wondering, ‘Did I really paint that?’ Though we have a good number of works hanging in the house, and I regularly flick through old exhibition catalogues, I notice that I tend to look at them in quite a superficial way, as if I am holding them at a distance somehow. This is partly due to my tendency to focus on their shortcomings, and the need to let finished work go. However, I suspect that the real reason is that I simply don’t know how to relate to them. It is possible that this disconnection reflects what was for many years a necessary split between my painting and the rest of my life. It may be that I unconsciously felt the need to separate and protect the anchor of my painting life from that unconscious sense of an abyss of nothingness within; otherwise I might become totally unmoored and lost.

As I have reflected on this account of my unfolding understanding of my journey, I notice that the insights shared have tended to be more generalised ones about the different bodies of work, rather than meditations on individual paintings. It was suggested to me recently however, that as part of this process of joining up the small and large fragments of my life and making sense of them, I might experiment with sitting before individual paintings and allowing them to speak to me and give up their long-concealed meanings.

I found this to be fascinating suggestion, and was curious as to why I had never contemplated doing so before. And so, over recent days and weeks I have spent time sitting before some of my paintings and opening myself to them, allowing feelings and passing thoughts to emerge unjudged and uncensored.

It was an extraordinary, though at times painful, experience. The paintings seemed to suddenly come alive and take on a new depth, spaciousness and intensity. On some occasions it was as if I was seeing them for the first time. I was flooded with a feeling of warm expansiveness, grounded in a tangible sense of solidity. It was like suddenly discovering that I have hundreds of old friends from whom I have become separated but who have been there for me all along. (They seemed almost like supportive angelic presences smiling at me knowingly.) I felt a sense of wonder and a quivering excitement at the possibility of suddenly being able to access all these doorways into hidden parts of myself. 16

This new sense of intimacy and connection is perhaps an awakening to what Jung called the ‘Inner Beloved’; the idea that there is a unique relationship within that is just as sacred and rich as any outer relationship. In ‘Man and His Symbols’ he writes,

“Union with the Inner Beloved fuses both the conscious and the unconscious, the objective and the relational, the particular and the transcendent. In accomplishing this union, one experiences love below the levels of persona (that which we receive from and project back to society), ego (that which we believe we are), shadow (that which we believe we are not), myth (those symbols we share with all humanity) to the level of Self (that which we really are, the central essence of the soul).” 17

Of course, this journey is a never ending one, and though I already feel more connected, solid and alive because of it, I recognise that I am still a beginner. As the psychologist friend who suggested this experiment wrote, ‘There is always more weaving and understanding and connecting and letting go (and letting come). Who we are is never definitive and trying to capture it is like trying to understand the flowing river by scooping out a handful of it.’ 18

Lockdown

May-November 2020

1 Robert McFarlane, ‘The Wild Places’ p. 88

2 Cecil Collins, Theatre of the Soul

3 Gary Lopez, Arctic Dreams

4 Etty Hillisum, A life Interupted

5 https://rubedo.press/propaganda/2013/8/15/rendering-darkness-and-light-present

6 Barry Lopez, ‘Arctic Dreams’, Harvill, p. 245

7 William Wordsworth, ‘Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood’

8 Heather Booth di Giovani, in an email, 27th August 2020

9 David Whyte, Consolations: The Solace, Nourishment and Underlying Meaning of Everyday Words, Canon Gate.

10 Jung understood the anima to be the unconscious feminine side of a man; the totality of the unconscious feminine psychological qualities that a man possesses. A projection is seeing an ideal of oneself, or qualities one longs to have, in a heightened fashion in another person.

11 Tuning into individual paintings in this way is something I have only just begun to experiment with. The process is explored further in the postscript on pages 15 & 16.

12 https://www.greekmythology.com/Myths/Creatures/Pegasus/pegasus.html

13 ‘To Learn from Animal Being’, John O’Donohue, Benedictus, Bantham Press

14 Job 12:7

15 David Whyte, Consolations: The Solace, Nourishment and Underlying Meaning of Everyday Words, Cannon Gate.

16 The thoughts about my 1992 painting ‘White Sea Pearls’ described in the section on ‘Longing’ are the outcome of one of these experiments.

17 The thoughts about my 1992 painting ‘White Sea Pearls’ described in the section on ‘Longing’ are the outcome of one of these experiments.

18 Michael Carroll in an email, September 2020